Photo compliments of A.C.

Dear Friends,

The first two books I was required to read during my first semester of college were Shakespeare’s Henry IV, parts I and II, and Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Shakespeare’s Falstaff had me rolling in laughter with his ribald declarations and bawdy antics. Frankl’s miraculous three year survival in Nazi concentration camps and the wisdom he later shared from his crucible moved me deeply, and the lessons have never left me.

Patrick+

More than memory

After twelve hours in the blowing snow digging out railway tracks, he was walking back to the barracks, his only protection from the whipping sub-freezing wind was his paper thin clothing. He was trudging along a path some ten miles northwest of Munich. The city was the festive site of boisterous Oktoberfests and avant-garde German art shows during his earlier days. He mused how a city of brightness could descend so deeply into darkness. He disposed of those thoughts, knowing where they would lead him. He exchanged them for thoughts about his wife, Tilly. Although shivering, he could envision the two of them enjoying tea in the warm sunshine of their Vienna garden. He was able to imagine her presence, as he admitted later, with an “uncanny acuteness.”

Continuing his painful trek, he contemplated Tilly’s face and felt her “frank and encouraging look — more luminous than the sun when it was beginning to rise.” What he did not know then was that his wife had already died of Typhoid Fever 400 miles away at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Victor Frankl, the lauded Austrian psychiatrist, perceived that even when a person is stripped of everything, as he was by the Nazis during WWII, a person can still find fulfillment — even “bliss” — as was his state during those long, frigid walks.

For Frankl, this was a powerful spiritual experience that preserved him through the unending onslaught of horrors in the four camps where the Nazis interned him: First, just nine months after his marriage in 1942, his family was deported to Theresienstadt, where his father died of starvation and pneumonia. Second, the remaining family was sent to Auschwitz, where his mother and brother were executed. Third, he was transferred to Kaufering, a subcamp of Dachau, where he endured his harshest labor duties — even digging an entire underground tunnel with crude tools and without assistance, And fourth, his final stop was Türkheim, another subcamp of Dachau, where, he too, contracted Typhoid Fever but somehow endured. On April 27, 1945, U.S. forces finally freed Frankl from Türkheim. His sister Stella was the only other family member to survive the holocaust. She had escaped to Australia before the mass deportations began.

Frankl was captive in concentration camps for three years, all the while he wrote on scraps of paper his observations of how human beings can persevere through such acute physical hardships and degradations. Once freed, he referenced his crinkled, brown fragments of paper and wrote his pioneering book, Man’s Search for Meaning. Franklin finished the entire first draft in only nine days. The German edition was published in 1946, but it was 1959 before the English version was printed. Straight away, Man’s Search for Meaning became a bestseller in the U.S. Shortly after, the book was translated into sixty languages worldwide. In 1991, the Library of Congress did an exhaustive study to discover that Frankl’s work is one of the most influential books in all of American history.

Prisoners break up clay for the brickworks at Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg, in 1939.

From emptiness to fulfillment

Confronted with the book’s success, Frankl was unmoved. He famously said that his book’s popularity was merely due to the "mass neurosis of our time,” which he described as a "private and personal form of nihilism," or more simply put — that people believe their lives have no meaning. He reasoned further that when life harbors no meaning for the individual, the way is paved for totalitarian regimes, such as the Nazis, to take power. On the more individual level, a person caught in a meaningless life will undertake a frantic pursuit of pleasure or work to distract him from the underlying emptiness.

Coming home to Vienna, Frankl observed that people, even after they survived the deprivations and degradations of the war, were tormented by addiction, anger, anxiety, and depression. To counter the emptiness he perceived in his patients, he developed a therapy known as logotherapy. Frankl adopted the name from the Greek understanding of the word logo, which translates “meaning.” The key to survive — indeed, thrive, he insisted — is the search for a unique purpose in life. Frankl repeated this mantra for the remainder of his life: “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how.’”

While carefully witnessing the daily lives of other captives in the concentration camps and honestly examining himself, Frankl developed his Three Wells of Meaning. He firmly believed that each person has been bequeathed their own unique purpose and personal strengths. The task before every human being is uncovering those attributes. Frankl’s Three Wells guide individuals in this task of self-discovery, which, in turn, will lead them to a life of meaning:

Through work, by creating or doing something that is meaningful for others and yourself.

Through love, by coming into contact with someone or experiencing something that is meaningful for others and yourself.

Through suffering, by undergoing suffering, which is unavoidable, yet taking a positive attitude toward it, which will prove meaningful for others and yourself.

Frankl was raised in a Jewish family, and as an adult he actively practiced his faith. His second wife, Eleonore Katharina Schwindt, whom he married after he returned home a widower, was as devout a Roman Catholic. The two of them attended both synagogue worship and Catholic mass and were known to celebrate both Hanukkah and Christmas. Reminders of his Jewish faith, such as quotes from prominent rabbis and quips from the Torah, are sprinkled throughout his writings and remembered by others from his conversations with them. Because of his fervent belief in transcendence, meaning that human beings can experience life beyond the normal physical level, Man’s Search for Meaning has continued to inspire both Jews and Christians to pursue meaningful lives since its publication three generations ago.

“Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how.’” Victor Frankl

Luke 10 and the pursuit of the meaningful life

Christians, for our part, may find that Jesus’ instructions in Luke 10 illustrate Frankl’s Three Wells of Meaning. The chapter is primarily focused on Jesus’ appointment of the seventy to precede him on his journey to Jerusalem. At the same time, Jesus’ instructions point the way for them to pursue a meaningful life. Unquestionably, several other foundational lessons can be found in the chapter. For now, we venture to perceive Jesus’ bidding to the seventy, as well as his encounter with Martha and his Parable of the Good Shepherd, through the lens of Frankl’s Three Wells of Meaning.

‘I send you as lambs in the midst of wolves’ Luke 10:1-24

The reader has a right to be confused at this point in Luke’s Gospel, for in the previous chapter, Jesus sent out the twelve to preach the kingdom of God and to heal (9:1-2). Why does Jesus now send out the seventy for much the same purpose and with equal urgency? The twelve refers to particular individuals, the apostles, who are specifically named by Jesus in Luke 6:13-16. The number seventy, on the other hand, signifies “completion or wholeness” in the ancient Jewish lexicon. The seventy are not individually named because the seventy represent all Christians throughout time. We, too, are appointed by Christ to work for him in communion with and for the benefit of others.

That all of us have been called to work for God is not a Biblical news flash. At the very beginning of the Bible (Genesis 1:27-32 & 2:15), God makes it clear that we are to work in His creation. One way of perceiving Eden, in fact, is as God’s immense tabernacle, with its massive blue domed ceiling in the sky soaring above the floor of his temple below — much like we experience a Medieval European cathedral. Looked at that way, human beings are not predominately portrayed as gardeners in the Genesis story but as priests ordained for His service in his tabernacle. God will make this calling clear in the second book in the Bible, Exodus. Having crossed the Red Sea to freedom and trekked through the desert for forty-five days, the Israelites arrive at the base of Mt. Sinai. Without delay, God summons Moses to him and explains within earshot of the people why He has led them to this isolated mountain in the middle of the desert:

You saw what I did in Egypt, and you know how I brought you here to me, just as a mighty eagle carries its young. Now if you will faithfully obey me, you will be my very own people. The whole world is mine, but you will be my holy nation and serve me as priests.

Exodus 19:4-6

God did not call Israel to Sinai to insist they “play right and be good boys and girls.” No, God’s calling to Israel transcends mere moral accountability. This complaining, ragtag bunch of escaped refugees have been chosen to serve as God’s priests in the world. The moral accountability of the Ten Commandments and its attendant demands describe the proper outlook and behavior of God’s priests in the world. As a side note, the number seventy (or seventy-two, if you count the outliers Eldad and Medad) has a precedent in Moses’ subsequent calling of the elders to assist him in leading the contentious Israelites in Numbers 11.

Getting down to work

‘Work to create something that is meaningful for others and yourself.’

‘The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few…’ Jesus bewails to his new recruits. Some Christians, surely not all, come to know that the work that will give our lives ultimate meaning is our service to Christ and his kingdom. With that truth in mind, I am reminded of a lesson I learned early in my Christian walk: “Christians have many different jobs, but all of us have one vocation, that is ‘to come to know Christ and then make him known to others.’” Vocation is derived from the Latin vocare, which means “to call.” Considered that way, we are all a bit like Superman or Zorro. During the day, Superman’s job was as a reporter for the Daily Planet. Zorro’s was to oversee his major land holdings, ranches, and farms. But their vocation and what gave their life meaning was to fight injustice. Our vocation is not far off the mark of these two fictional heroes. Jesus commands the seventy to ‘heal the sick and say to others, “the kingdom of God has come near you today.”’ Those are our marching orders, too. Our love for God moves us to step out in some small or big way to lessen the pain of someone or a lot of someones, and instead of etching a big “Z” in the dirt or across a villain’s shirt, tell them it’s a gift from God.

Writing this, I am reminded of the four hospice nurses, three females and one male, who attended to our forty-three year-old daughter as she was nearing her death in early July. All four, without coaching, told Kay and me that this is the work to which they had been called. Imagine that, reporting to work each day or night for the sole purpose of nursing a person through their last hours. Quietly visiting our room every hour and a half, they were determined to minimize our daughter’s suffering, and, at the same time, assuage her parents’ excruciating heartbreak.

Most of us do not have a vocation of that intensity, but every one of us is called byChrist to step into the breach in some way. I marvel at the greeters who serve at St. Boniface Church in Comfort, TX on Sunday mornings. One of the greeters last Sunday was on a walker. Two weeks ago another greeter served from a wheelchair. When a visitor walks into our church and is met by a man in a wheelchair or a woman on a walker, they may suspect that they are walking headlong into the kingdom of God.

Love is stepping up and sticking around

‘Love by coming into contact with someone or experiencing something that is meaningful for others and yourself.’

Jesus instructs the seventy to stay where they are welcomed, ‘eating and drinking what your hosts provide.’ These are not primarily logistical instructions. Jesus wants the seventy to love those they encounter. Marriage primers often repeat the adage — “love is a verb.” We all know what happens when someone shrinks love to a feeling, because our feelings come and go. The seventy are to model the opposite of that. They are to stay and make themselves at home with the families who receive them. We have probably overused the term — “ministry of presence.” Nevertheless, much is to commend the substance of that saying. To love another is to be with that person, to stick around through thick and thin. I have two friends from high school. We have stuck together for fifty-six years. We show up for one another during the good times, but also for the bad. For one of the two, Mark, I have buried both his mother and his nine year-old son. Both of my friends have been by my side and constantly in phone contact when I buried my brothers, sister, mother, and, now, our daughter. I am not exaggerating when I say they have carried me through these hard days.

Twenty years ago, another female friend of mine caught me up short when she said, “Pat, pastors grossly overestimate what they can do in five years and vastly underestimate what they will do in ten.” Until she said that to me, I considered myself sort of a blitzkrieg pastor. I was known for “fixing” churches after they underwent painful trauma and significant loss of membership and support. I figured I could rush in, repair the problems, and rush out once the pews were filled and the bank account was in the black. That’s treating other Christians like broken kitchen appliances — not like people you love. The key is to stick around. Eat, drink, cry, laugh, mourn, rejoice, sing, pull weeds, know each other’s kids, their parents, their good side, and their bad side. When we love like that, the kingdom of God has come near.

‘I’m where I’m supposed to be.’

‘Undergo suffering, which is unavoidable, yet take a positive attitude toward it, which will prove meaningful for others and yourself.’

To risk love is to suffer. Put yourself out there and you’re open to a world of hurt. Jesus is frank with the seventy: not everyone wants to see you. Some, in fact, will despise you. The seventy can shake the dust from their sandals, but having the last word won’t lessen your pain. Rejection and mistreatment always hurts. I think about Victor Frankl surviving, not one, but four Nazi concentration camps over the course of three long years. At one point, he tells the story of walking along an icy trail while being beaten repeatedly by one of the particularly malevolent prison guards. A man walking beside him whispered. “I’m glad our wives can’t see us now.” Frankl thought about the man’s comment and realized that he actually wanted to “see” his wife at that moment. So, he did. As this became his survival practice, he visualized her most vividly when he was suffering the worst. By doing so, he discovered that his suffering could have meaning. Mentally and spiritually he could transcend his circumstances, and no one, not even the nastiest Nazi guard, could stop him.

When Catherine Grace was admitted to an in-patient hospice, our forty-seven year-old son Clay was already packed up and ready to lead a ministry team to Tanzania. Everything was set for him to go — airline tickets, detailed instructions, and a full retinue of eager volunteers. Hearing the news about his sister, Clay backed out of the journey to Africa at the last minute, giving the coveted leadership position to another. Instead, he arrived to be with us just as Catherine Grace was dying. Kay, Clay, and I were together with her at the last. All three of us fell apart with sobs far more guttural and raw than I ever heard voiced from any of us…but we were together, the three of us, sprawled across Catherine Grace’s hospital bed.

Later, when Kay and I were able to get our emotions somewhat under control, I said to Clay, “Son, it’s okay for you to rebook your flights and catch up with your mission team in Tanzania.” He peered at me and plainly stated, “I’m where I need to be.” In those six words, Clay described how we transcend suffering. Rather than constantly bemoaning our misfortune and furiously trying to escape it, we take a positive view that, if not then, perhaps later, deeper meaning will emerge from our pain…and Satan will fall like lightning from heaven.

Love that goes up and out Luke 10:25-42

Of course, if we extend ourselves into the lives of others, we are susceptible to more pain. We will experience more joy, too, but pain will emerge from time to time. In the Parable of the Good Samaritan (10:25-37), this expands the bounds of love for his followers. We have grown so accustomed to Jesus’ parable that we have drained its power and refashioned it into a Hallmark movie clip. However, the story’s plot would have been scathing to the ears of Jesus’ 1st century hearers. The fact that a despicable Samaritan would come to the aid of a wounded man would have grievously insulted their moral foundations. As the Samaritan approaches the beaten and bleeding man, you can almost hear the film score for Jaws in the background. Yet the Samaritan is the only one who steps up. The two professional religious men won’t risk the encounter.

The one person who should not have been surprised by Jesus’ parable is the one who cannily asked, “Who is my neighbor” in the first place. Luke identifies the inquisitor as a lawyer, which means he was an expert in the five books of the Torah and far more educated in the Scripture than Jesus or any of his disciples. A few moments earlier when prompted by Jesus, the lawyer immediately recites the Great Commandment, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind. And you shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ The lawyer drew the first part of his answer from Deuteronomy 6:4-5, and pulled the second part from Leviticus 19:18 —books three and five of the Torah.

The passage from Deuteronomy 6:4-5 has long been known by Jews as the Shema — “Hear!” The Shema is the foundation of Moses’ second and longest speech recorded in Deuteronomy. He eventually delivers three speeches 1:1-4:43; 4:44-28:68; and 29:1-30:20 to Israel before he retreats to Mt. Nebo to die. Then as now, the Shema rises up as God’s most fundamental instruction to Israel and us: We are to love God beyond all other people and things that continuously vie for our devotion. Likely, you have been to a Jewish friend’s home to find a mezuzah (Hebrew - “doorpost”) affixed at a slant on the doorframe. Inside the mezuzah is a piece of parchment with the expanded Shema printed:

Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. Keep these words that I am commanding you today in your heart. Recite them to your children and talk about them when you are at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you rise. Bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates. Deuteronomy 6:4-9

The Good Samaritan, by Jacob Jordaens, 1616

The Shema, in fact, forms the crux of Jesus’ response to Martha at the dinner party she hosts for him after his encounter with the lawyer (10:38-42). Martha is scurrying around trying to make the occasion perfect, while her sister sits with Jesus and the men — not her place in that 1st century world— nevertheless, she is intent on taking in Jesus’ every word. Martha stomps into the room and demands that Jesus scold her sister and command her to get up and help with the supper, which seems a reasonable request. Instead Jesus admonishes her, ‘Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her.’ Jesus knows we are distracted by many things. Even good things, seemingly noble enterprises, can slyly seduce us away from our first love — God. When that happens, our reservoir of love for every thing and everyone else is depleted. The love of God is our spiritual fuel that thrusts us outward to love even the seemingly unloveable.

It is this outward thrust of love God pours into our hearts — even for those deemed unloveable — that circles us back to the encounter with the lawyer. Because of his keen facility with the Scripture, the lawyer would have readily known that the second passage, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself, is closely followed in the same chapter by God’s command to love those most Israelites considered abhorrent: The alien who sojourns with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself; for you, too, were aliens and strangers in the land of Egypt. I am the LORD your God’ (Leviticus 19:34). The Parable of the Good Samaritan simply restates a foundational truth in the Torah: No one is considered out of bounds from the love God has poured into our hearts. Christians and Jews are commanded by God to extend our love beyond cultural, ethnic, and national barriers into a world that is cruel, dehumanizing, and hurting terribly.

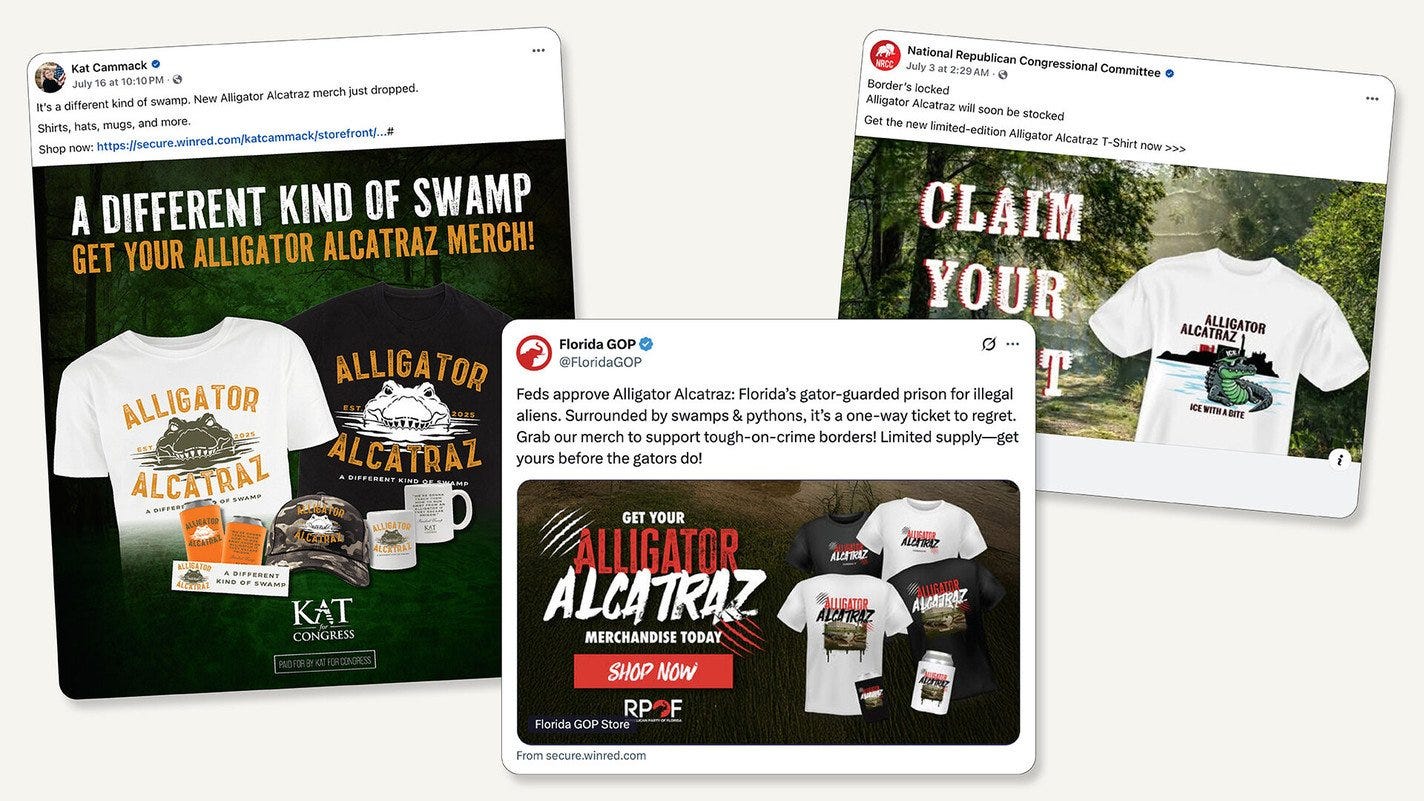

In the land of gators, snakes, and mosquitoes

Alligator Alcatraz, as it has come to be known, evokes for me the visages of Jesus’ lawyer inquisitor and Victor Frankl. The thirty-nine square mile, tent-city immigrant detention center sits squarely in the middle of the Florida Everglades. Because it has no running water or electricity, it is dependent on generators and trucked in water. Ironically, the tents erected there are those used for parties and wedding receptions, but these are not full of brightly decorated tables laden with refreshments but with gray galvanized steel cages containing women and men. Currently, there are 1,000 persons interned there. Plans have been made to add 4,000 more. The mosquitoes are so thick that you cannot open your car window for even a second without inviting scores of bites. Imagine what it is like in the tents — especially at night.

Some people in Florida are waking up to the certainty that Alligator Alcatraz is not full of gang members and violent criminals but of neighborhood maids, local custodians, hard-working construction workers, and compliant families who appeared for their regular immigration court hearings. Even the most zealous Republican and callous American recognizes the facility was not built for anything other than exacting cruelty and inciting fear.

A federal agent takes a man into custody at 26 Federal Plaza. Dozens of people have hearings in New York’s immigration courts each day, and now face the possibility of being arrested just by showing up, regardless of the status of their cases. Photo compliments of Reduxx.

Thankfully, not every Republican is on board with this barbaric enterprise: “Arbitrary measures to hunt down people who are complying with their immigration hearings is not what we voted for,” the co-founder of Latinas for Trump wrote on X in June. Conditions at Alligator Alcatraz resemble prisons in places their grandparents escaped in Cuba. “Pick them up, throw them out, but don’t mock them,” one veteran Republican says of criminal immigrants. Alligator Alcatraz - The Economist

Equally disturbing is that Alligator Alcatraz is not staffed by professional correctional officers. Instead, those who respond to flashy advertisements are quickly trained on-site. Suddenly, the entire project is reminiscent of Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, and Auschwitz, where club-wielding kapos enforced the Nazi’s brutality. Could the United States be edging ever closer to the inhumane barbarism inflicted on Victor Frankl and millions of innocents by the Third Reich?

American Christians, whether we are conservative or progressive, should stand shoulder to shoulder with the lawyer who asked, ‘Who is my neighbor?’ 1,000 cries desperately resound from the Florida Everglades.

Another great writing! Thank you, Pat. Your reiteration and illumination of Our Lord's teachings are appreciated. Love and blessings to you and yours, Unc Bill.